November 2019 was certainly an eventful month for Venice. As a current resident in this sinking city, a lot of questions have been put to me recently; why is Venice flooding? What is Acqua Alta? Are you okay? And my personal favourite: Did you remember a wet suit?

Acqua Alta itself is not an anomaly to the Venetian lifestyle. With the literal translation of ‘high water’, between the months of October and February, the water levels in the lagoon of Venice rise higher than normal. Normal water levels stand at around 60-70cm, with the ability to reach 100-120, however this year it brought levels of 184cm, the highest recording in 50 years. Acqua Alta occurs as a result of the spring high tides and, this year, with the addition of a meteorological storm surge driven by the strong sirocco winds blowing north-eastern across the Adriatic Sea, the levels were extreme.

November 2019 saw the highest levels of Acqua Alta in Venice since 1966, with nearly record-breaking figures. During the late hours of 12th November, Venice was transformed into a scene straight out of an apocalypse film, with water levels continuing to rise and wreak havoc on the city. This melodramatic sentence might cause doubt in some of your minds, however, let me assure you, it wasn’t pretty. During the months of Acqua Alta, it becomes a typical routine to wake up and check, not only your weather app but also the tide apps (h!ghtide is a solid option) every morning. Here you can find an easy access point to exact levels of water across the island and a recommendation for the type of footwear needed that day; be it trainers, wellies or a wetsuit! Ok, so maybe not actually a wetsuit, but this app truly can be a saviour against cold feet! Water levels are colour-coded in three levels to signify the risk of the situation. Nonetheless, these are not the only signals that Venice has to judge the severity of these events, as Venetians are not unaccustomed to the sound of sirens being blared across the island at an early hour of the day. The sirens, which date back to 1945 when they would signify Allied aircraft bombing the harbours, are still used today to alert inhabitants of the dangerous rising tides. Despite the history of high tides, Luigi Brugnaro, Mayor of Venice, declared Venice to be in a state of disaster following the events of this year. St Mark’s Square, one of the lowest parts of the city, was one of the worst-hit areas, with St Mark’s Basilica flooding for only the sixth time in the past 1,200 years. Brugnaro commented: “The situation is dramatic. We ask the government to help us” as he urged Venetians and tourists to share their stories and images of the flooding so that the government would provide more assistance to the situation. Three sunken vaporettos (water buses), dozens of boats stranded in random streets, walls torn down, shops, hotels, and restaurants all wrecked; it was clear that the city had suffered “grave damage”, as its Mayor suggested.

Photograph: Marco Bertorello/AFP via Getty Images

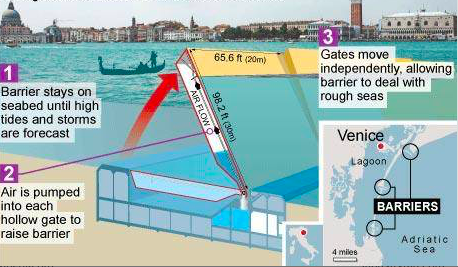

Whilst we should avoid attributing a single event to climate change, the increased frequency of these exceptional tides is reason to be concerned. The combination of a changing climate, rising sea levels and a city that is already sinking is far from ideal. However with this being said, as a result of climate change, the jet stream that drove the Adriatic storm towards Venice will become more frequent and therefore increase the likelihood that Venice will flood more gravely, during the season of the higher spring tides. Venice’s mayor stated that the recent events were, in fact, a result of this and “Now the government must listen, these are the effects of climate change…the costs will be high”. To combat such events occurring more frequently, the city has undergone a project to protect itself. Beginning in 2003, the Mose Project has intended to protect the city from excess flooding through creating an integrated system, which will consist of rows of gates installed at the outer islands, Lido, Malamocco and Chioggia, which would temporarily isolate the Venetian lagoon from the Adriatic Sea and ultimately the high tide. Alongside other measures, including coastal reinforcement and the improvement of the lagoon itself, the Mose project should have the capacity to protect the city from tides of up to 3m. By 2013 reports were announced that claimed more than 85% of construction was completed, yet due to soaring costs, scandals and delays the initial deadline of 2018 was missed and efforts are now being redirected towards a 2022 finish.

Once water levels had returned to a ‘safe’ level, the community of Venice rallied together to begin the momentous clean-up project. From tracking down misplaced gondolas to vacuuming water out of hotel lobbies and clearing up debris from torn down canal walls, the sense of community was as strong as ever. The Erasmus Student Network at Ca Foscari University offered to lead walking groups of students to the worst affected areas to help clean up, which allowed so many foreign students to feel like they had played their part in the city that they had learnt to call home for their placement abroad.

A month on from then, the city is back and in full swing. Granted that wellington boots or plastic bag replacements are still low in stock, the city has bounced back outstandingly. However, additional pressures on the impending finish of the Mose Project are critical to avoid such costs in the future. Whilst these events were indisputably intimidating, it was patently an experience. Also, a reason that I am very happy to live on the mainland!

© S R D HILL

One response to “Acqua Alta: The Rising Tide”

Very interesting and informative article well written by SOPHIA.

LikeLike